A novelist, screenwriter, television personality and half the creative genius behind the Fight Card series, Paul Bishop recently finished a 35 year career with the Los Angeles Police Department where he was twice honored as Detective Of The Year. He continues to work privately as a deception expert and as a specialist in the investigation of sex crimes. His books include the western Diamondback: Shroud Of Vengenace, two novels (Hot Pursuit / Deep Water) featuring LAPD officers Calico Jack Walker and Tina Tamiko, the thrillers Penalty Shot and Suspicious Minds, a short story collection (Running Wylde), and five novels in his L.A.P.D. Detective Fey Croaker series (Croaker: Kill Me Again, Croaker: Grave Sins, Croaker: Tequila Mockingbird, Croaker: Chalk Whispers, and Croaker: Pattern of Behavior). His latest novel, Fight Card: Felony Fists (written as Jack Tunney), is a fast action boxing tale inspired by the fight pulps of the ‘40s and ‘50s. His novels are currently available as e-books.

Continuing our look at the hope and appeal offered by fight fiction …

Paul Bishop

As the ‘70s progressed, the public became primed for a change in their fight fiction. Unlike with prior generations, this change in popular entertainment would not be tied to the socio-economic factors of the day. Instead, a blurring of the lines of fact and fiction – especially in the world of boxing – was occurring, reflecting the hyper embellishments of celebrity being inflicted upon larger popular culture as a whole.

In boxing, the anger, power, and sheer showmanship of Muhammad Ali – the man who would become boxing’s greatest ambassador – had revitalized the public’s fervor for ring action. Ali’s larger than life love-me-or-hate-me-I’m still-The-Greatest personality overshadowed the ever darkening machinations of the trademark spiky-haired head and grasping fingers of promoter Don King.

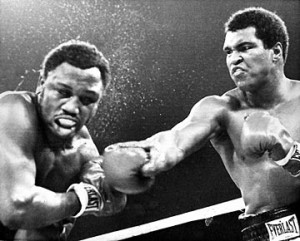

In 1971, Joe Frazier fought Ali in a bout hyped as The Fight of the Century. Frazier prevailed over Ali, who was returning to boxing after being suspended for over three years for his refusal to obey the draft. The defeat sent Ali on a quest, fighting contender after pretender to the heavyweight throne in an attempt to obtain another title shot.

The Rumble in the Jungle in 1974, pitted then world Heavyweight champion George Foreman against former world champion and challenger Muhammad Ali. This fight, coupled a year later (1975) with the climax of the bitter rivalry between Ali and Frazier – dubbed The Thrilla in Manila – returned boxing to the world stage like nothing that had gone before.

Norman Mailer’s bestselling non-fiction work, The Fight, documented the greatest fight of the greatest life with all the power of a great fictional narrative, ushering in a culmination of self-involved journalism. All of which laid the ground work in preparing the public for the little film that could go the distance … Rocky.

Rocky not only detailed the winning underdog story of a fighter who only wanted to go the distance – an achievable, if difficult, goal believed in and desired by the everyman of the day in his everyday mundane life – but was, in the actual inception and creation of the film itself, an underdog story to rival its fight fiction plot. Sylvester Stallone was inseparable from his onscreen persona as he fought for his screenplay and starring role against all studio odds – and then went the distance as Rocky would go on to win three Oscars ©, including Best Picture.

Rocky and its (eventually) five sequels were hits and misses with the critics, but not with the public. The average Joe began to see the hype of the real world fights and fictional movie fireworks as almost one and the same.

Fight stories were back in the public eye in a big way.

In 2000, fight fiction morphed yet again with the publication of the pseudonymous F.X. Toole’s, Rope Burns: Stories From The Corner. Each story in the collection was a gem. But unlike the tales populating the fight pulps of old, the stories in Rope Burns gave a whole new human face to the world of boxing, a deeper meaning – all leading to the brilliant Best Picture Oscar © winning film Million Dollar Baby, based on several stories from the collection.

The stories in Rope Burns proved to the wider public, yet again, what fans of fight fiction have always known – the world of the sweet science, at its best, has always been a reflection of what it means to be human, what it means to struggle, what it means to be hit in the face with the daily and millennial challenge of survival as individuals, as families, and finally as a race.

In the new millennium, the economy is struggling again. Today, the ever exploding popularity of mixed martial arts tournaments (MMA) has again brought the fighting arts back to the forefront of the public consciousness. In MMA, the everyman sees in the caged octagon a release of his or her own frustrations at the state of the world – the stark struggle to survive in a time and place where the rules have change, where the action is faster, more brutal, and yet possessed of a choreographed beauty.

Simultaneously, the thirst for fight stories has also increased, as shown by the popularity and critical acclaim for such MMA-themed novels as Suckerpunch by Jeremy Brown, The O’Quinn Fights by Robert Evans, The Longshot by Katie Kitamura, Choke Hold by Christa Faust, and many more.

Traditional boxing novels are also flourishing. Every Time I Talk To Liston and Las Vegas Soul by Brian DeVido; Pound For Pound, F. X. Toole’s posthumously finished novel; Waiting for Carver Boyd by Thomas Hauser; and more, continue to tell the tale of the tape and the story of the squared circle.

By the end of 2013, the Fight Card series (along with spin-off brands Fight Card MMA and Fight Card Romance) will have published twenty-seven plotted tales of fistic mayhem from some of the best New Pulp authors working today, each sporting a stunning cover created by artists Keith Birdsong and David Foster.

2014 will also offer a full slate of monthly Fight Card titles, including more tales from the Fight Card MMA and Fight Card Romance imprints along with more of the traditional Fight Card tales set in the noir-filled streets of the earlier decades.

Retro or modern, Fight Card novels will continue to provide inspiring, entertaining stories of tough guys caught in tough spots with nothing but their fists, wits, and fighting nature to battle against the odds. The Fight Card novels are about characters and their individual journeys and how they can inspire our character and our journeys.

As Fight Card readers you can become part of the Fight Card team by writing reviews on Amazon with your honest opinions of the tales you’ve read, giving us shout-outs on your blogs, and visiting the Fight Card website at www.fightcardbooks,com/