This refrain comes up again and again when talking to my writer friends (and not always initiated by me): something worth doing is worth doing well. It’s certainly not a controversial idea, though talking about it is not without its risks (as writer myself, I will not be providing examples of poor work to avoid shooting myself in the foot).

Put another way: we as an industry are going cheap, and it shows.

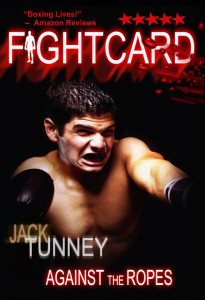

Usually it starts with the cover—bad art, or weak stock photos, with poor typography. If the cover is bad, the inside is often worse—poor layout, weak font choices, text that’s too small to read, or so big you could read it from across the room. The interior art looks fuzzy, or way too dark. Maybe there’s nothing in particular you can put your finger on, but something just isn’t right—very possibly the paper itself is poorly chosen (or left unconsidered).

Overall, you’re left with a feeling of cheapness—and it’s probably true: not enough money and attention has been put into this product.

Like it or not, this lack of detail negatively impacts the stories themselves. Fewer people will buy the book, and some people will be so turned off by the experience that they will set it aside for good. All of this, regardless of the quality of the stories themselves.

It would be easy to lay blame at the feet of self-publishers, but it’s not limited to that world. Poor quality runs throughout all levels of publishing, at least sporadically, from indies to the big names.

The blame for this lies in a few areas.

Budget

It’s been said that there’s little money in publishing, and perhaps that’s true. Spending much on something with little chance of seeing it returned doesn’t make too much sense. To create a work of quality, it does take skill (or money to hire that skill). We are at a point where it requires little to no money to produce books, even printed books—from ebooks to print on demand, a publisher does not need to outlay much cash to get a book to a reader and see a return on investment. Unfortunately, this low-budget approach shows all too often.

Too Many Hats

I’m a jack-of-all-trades kind of guy: I have an art background, I work as an illustrator and designer (and animator, and video guy, and…), I’ve done some sound work, I write. I understand there are people (and publishers) out there that can handle the whole shebang and do a fine job of it. The thing is, the vast majority of people can’t, and even those that can generally are not great at everything—I know this, all too intimately. If you’re trying to take it all on, you probably shouldn’t.

Plus, if you are taking on all of the roles, you will generally suffer from tunnel vision, and miss out on glaring problems. As the wearer of all of the hats, you are probably working in a vacuum, and regardless of problems with teams (group think, lowest common denominator results), more people means more eyes on the end result.

Another quick point here: I’m a big believer in using the right tool (or software) for the right job, but just having that tool does not make you a master of it (and mastering it still doesn’t make you a designer).

Quantity vs. Quality

Perhaps this is a flawed perception, but it appears that some go for the shotgun approach: more products offered, more sales. It may be accurate, too—I haven’t looked for research to disprove this notion—but it seems to me that spreading money across fewer books (and thus more per book) would significantly improve the end results, and the financial gains from each. No doubt there’s a tipping point, where a piece goes from appropriately treated to collector’s edition (with a price to match)—but if this is your concern, this article isn’t really aimed at you.

Contrary to what it might sound like, I’m not trying to say “you all suck!” or that I want fewer books around. I love all kinds of books, and I want to see the publishing world do better by delivering better.

There are solutions to these problems, and not all of them require more money spent (though some expectation of investing in a work should be assumed). Educating yourself, spending smarter, hiring the right people, finding others who will give you honest opinions…these are all steps in the right direction.

And these are all planned future posts. Stay tuned.